Oops! Government got it very wrong

Years after Mineral Resources and Energy minister Gwede Mantashe fought against allowing wider embedded power generation in South Africa, new projects are set to explode in the country – realising the pent-up demand the minister said didn’t exist.

In a parliamentary Q&A this past week, electricity minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa noted that, since the removal of the threshold for embedded generation in South Africa, the private sector has initiated over a hundred projects aiming to bring up to 12,000MW online – with 66,000MW in the pipeline.

“The pipeline of confirmed private sector generation projects has increased to 126 projects representing more than 12,000MW of new capacity since the amendment of Schedule 2 of the Electricity Regulation Act to remove the licensing threshold for generation facilities,” Ramogkopa said.

“1,338MW is expected to connect to the grid in 2023 and 3,081MW in 2024. A survey by Eskom showed that the total number of projects in the pipeline is 66,000MW.”

The number of private sector projects in the pipeline is staggering. While transmission and grid capacity constraints from Eskom’s side remain a significant challenge to making these projects a reality, it is clear that the demand for alternative energy is there.

The numbers are particularly astounding when considering that, until 2023, any embedded generation projects were restricted to 100MW. And until August 2021, they were restricted to just 1MW.

It’s also worth noting that the process to remove these limits was fought by the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) every step of the way.

The biggest hurdle

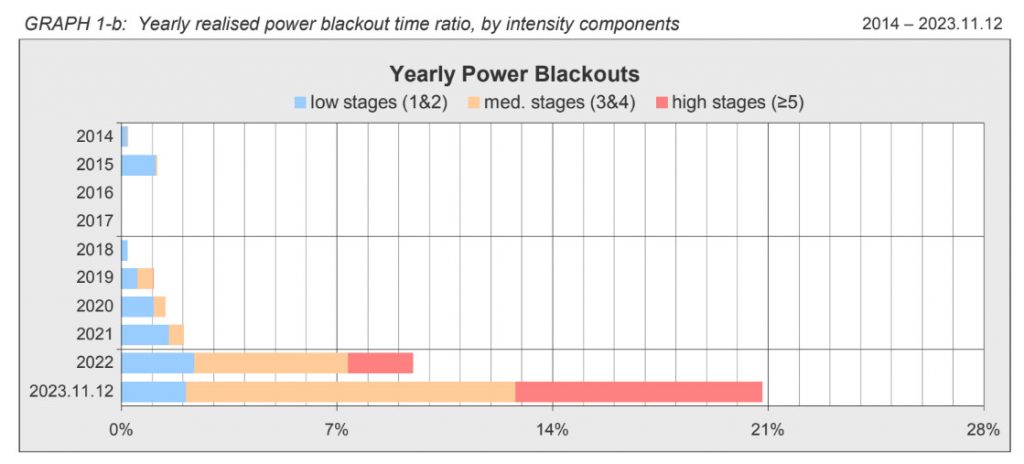

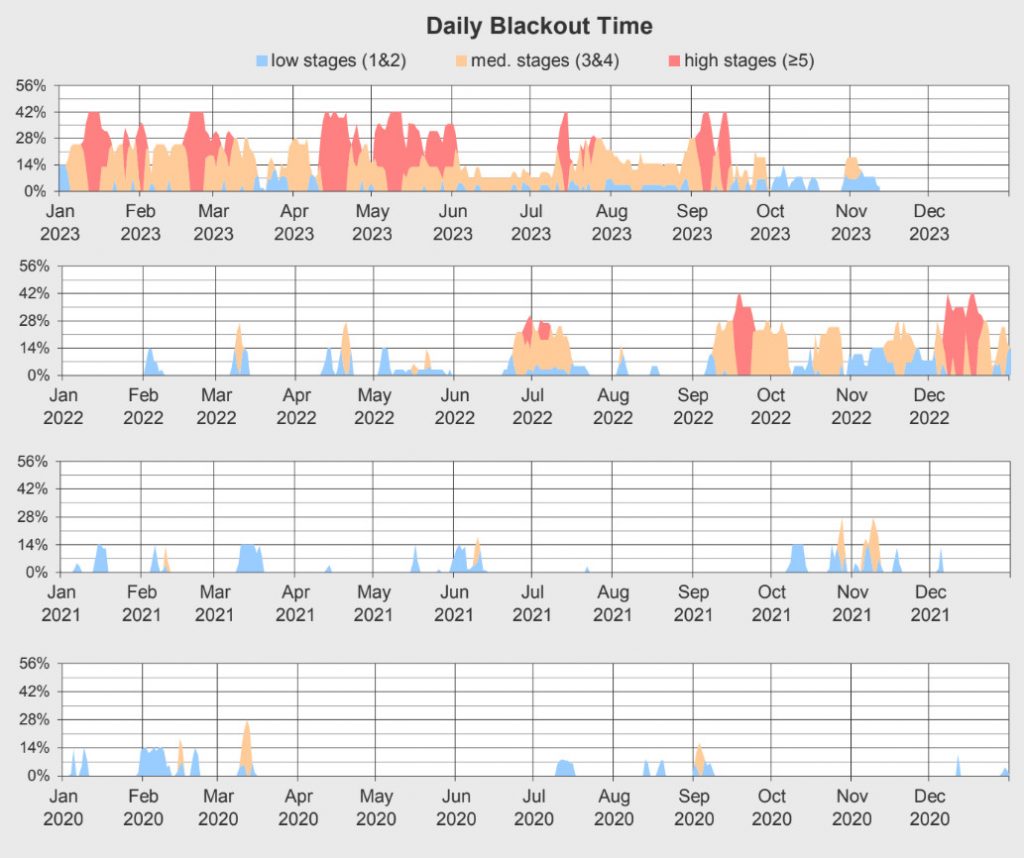

When permanent load shedding struck South Africa in 2022, the country was already neck-deep in the power crisis, with the room flooding fast.

Unfortunately, the country had been stuck with both its feet in cement blocks and its hands firmly tied behind its back thanks to onerous and restrictive energy regulations that prevented anyone but the state from doing anything about it.

Until 2021, South Africa’s energy regulations required any embedded generation project to have to go through expensive and burdensome registration requirements. Any embedded generator that produced more than 1MW of energy had to be registered with the national energy regulator Nersa.

After suffering “the worst load shedding ever” (at the time) in 2019, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy came under pressure from the private sector to increase this cap from 1MW to 50MW.

However, Gwede Mantashe – who took over as DMRE minister in 2019 – pushed back against these proposals, saying that the private sector was “not ready” for 50MW projects and that if any extensions to the threshold were made, only 10MW was needed.

Despite talking about expanding the threshold, the department kept the 1MW level in place in the 2019 IRP. Mantashe argued at the time that many private generators would end up producing more power than they needed – and this excess would have to be sold, which required a licence.

He was adamant that 1MW was enough. 2020 quickly went on to become the new “worst year of load shedding ever”.

The first big move on embedded generation only came when President Cyril Ramaphosa, faced with another record year of load shedding, launched Operation Vulindlela, which aimed to fast-track new generation projects by opening up the market.

Mantashe described this move by the president as “twisting (his) arm” in this direction – implying his opposition to the change – and he was ultimately forced to acquiesce and raise the threshold to 100MW – a massive leap from the 1MW or proposed 10MW before.

The threshold was officially changed in August 2021, but it was far too late to do anything meaningful as new generation projects take at minimum 18 to 24 months to come online. 2021 went on to be yet another “worst year ever” for load shedding.

2022 saw another major shift, however. As load shedding entered its “permanent state” in September 2022, Ramaphosa decided to eliminate the threshold entirely.

The threshold was only officially removed at the start of 2023, and 2022 was another worst year ever for load shedding, and 2023 is already way past being the worst year on record – but hope springs eternal that 2024 will finally be a positive turn.

Now, almost three years after arguing that there was no demand or need to open the market to private embedded generation, the market appears to be flooding with projects.